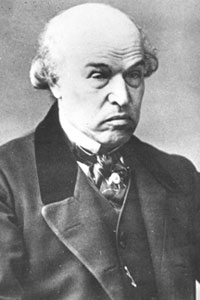

William Jenner, Great Ormond Street's First Physician

While Dr Charles West is acknowledged as the founder and inspiration of the Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street, he had a lot of help from the Great and the Good in its planning and early management. One of the most important of these supporters was William Jenner (1815-1898), who joined the hospital as its first physician.

The fourth son of a Kent innkeeper, Jenner was a relentlessly ambitious and hard-working doctor. As a young man, he had specialised in gynaecology, (and this may have been how he met Charles West), before turning his attention to pathology. In the 1840s he worked at the London Fever Hospital in Islington – at that time the only hospital for infectious fevers – and began to take an interest in typhus and typhoid fevers. In the English-speaking world at that time these were widely believed to be the same disease (in spite of French researchers having shown that they were separate), but in 1849 Jenner confirmed that they were indeed two distinct diseases, with quite different causes. His monograph on the subject earned him an international reputation. Public health officials could now concentrate on eradicating typhus by controlling the human flea population, and on getting rid of typhoid (or enteric) fever by devising methods to purify the water supply.

The fact that William Jenner joined the Hospital for Sick Children at its birth, and at a time when his own reputation and public profile was growing, was an enormous boost to the Hospital and did much to silence its critics in the medical profession. His private patients numbered the wealthiest and most influential members of society, and it is possible that he was responsible for interesting his neighbour, Charles Dickens, in the workings of the children’s hospital. He used his experience at Great Ormond Street to write classic studies of rickets and diphtheria (then a major cause of child deaths), and only gave up his post when he was appointed physician-extraordinary to Queen Victoria in 1862. Although he was no longer on the staff of the Hospital, he remained on the Management Committee, having, “withdrawn neither his good wishes nor his good offices.” It could have done Great Ormond Street no harm at all to have as a stalwart supporter someone who had the ear of the monarch. When Victoria and her children sent toys to the hospital each Christmas, it was Jenner who went through the boxes, checking that they were safe for the patients.

Typhoid played a major part in his relationship with the Queen, as he treated Prince Albert through his fatal encounter with it in 1861, and attended the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) when he contracted typhoid ten years later. As a mark of her gratitude, he was created a baronet in 1868, and promoted within the Order of the Bath several times before his death. He held many significant hospital and professional appointments, and was a teacher of genius, delivering his observations in a such scrupulously precise way, that his students remembered his exact words for the rest of his lives. His views on the role of the doctor with regard to the patient echoed the philosophy at Great Ormond Street,

“…So far as concerns the non-professional public, the aims and objects of medicine ought to be: to prevent disease, to cure disease, to prolong life, and to alleviate physical suffering”.

Jenner (like West) was a difficult character when it came to dealing with colleagues. A workaholic, he once responded to a question as to what he did for amusement with, “Amusements! My amusement is pathological anatomy!” He achieved great eminence in his profession (for six years he was President of the Royal College of Physicians, and was described by one author as ‘the virtual dictator of his profession’), and was showered with public honours at home and abroad. However, he formed opinions very rapidly, and hung on to them in spite of being shown to be in the wrong. In 1878, he threatened to resign from the British Medical Association if women were admitted as members, and he had some long-running feuds with his peers. However, like Charles West, children adored him – in spite of his deeply unprepossessing appearance. One tale often told by Charles West about him has survived down the years: a patient at Great Ormond Street said to him, “You are so like my daddy!” Jenner was flattered, until he caught sight of the boy’s father, who was, “most villainously ill-looking”. Nevertheless, he took the comparison as the compliment the child had intended.