Supporters of The Hospital for Sick Children since 1852

When The Hospital for Sick Children opened in 1852 it was assumed that the majority of its income would come from its supporters through individual donations and subscriptions, a situation which remained essentially the same until the formation of the National Health Service in 1948.

Those supporters who contributed above a certain amount qualified as Honorary Governors or Life Governors, which entitled them to nominate a number of patients for admission annually. Queen Victoria gave £100 when the Hospital opened, with smaller contributions from other members of the Royal Family. From 1858 to the 1890s, the Hospital’s annual Festival Dinner was an important source of income, with notable speakers, including the Prince of Wales, Charles Dickens, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Oscar Wilde and John Walter, the owner of the “Times”. At their peak the events raised one-third of the Hospital’s annual income.

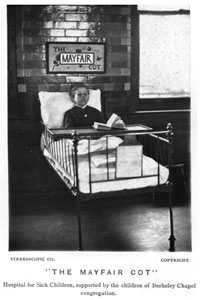

From 1868, commemorative cots became a notable addition to the hospital’s income, with beds being sponsored either for a fixed term, or, for a donation of £1,000, in perpetuity. The cots were endowed by a wide variety of individuals and organisations, including several by Mrs Gatty (the founder of the children’s magazine Aunt Judy) and members of her family, several by the Anglo-Armenian magnate Sir Basil Zaharoff. Other celebrities to have cots in their name included Lewis Carroll, Enid Blyton, children’s book-illustrator Kate Greenaway and the racing driver/land-speed record holder Parry Thomas. The latter’s cot was named “Babs” after his car. Sponsorship of cots was not restricted to rich and famous: the Mayfair Cot (pictured right) was sponsored by the children of the congregation of Berkeley Chapel.

From 1868, commemorative cots became a notable addition to the hospital’s income, with beds being sponsored either for a fixed term, or, for a donation of £1,000, in perpetuity. The cots were endowed by a wide variety of individuals and organisations, including several by Mrs Gatty (the founder of the children’s magazine Aunt Judy) and members of her family, several by the Anglo-Armenian magnate Sir Basil Zaharoff. Other celebrities to have cots in their name included Lewis Carroll, Enid Blyton, children’s book-illustrator Kate Greenaway and the racing driver/land-speed record holder Parry Thomas. The latter’s cot was named “Babs” after his car. Sponsorship of cots was not restricted to rich and famous: the Mayfair Cot (pictured right) was sponsored by the children of the congregation of Berkeley Chapel.

In some cases, complete wards were sponsored by individuals, notably the Dresden Ward (funded by a gift of £25,000 in 1901 from the estate of the city merchant Edmond Dresden), the Annie Zunz Ward (supported by a legacy of £3000 and later additional sums from the estate of metals dealer Siegfried Zunz), the American Friends ward and the Gas Light & Coke Company Ward.

Punch Magazine also endowed a ward, and ran regular fund-raising campaigns for the Hospital, in late Victorian and Edwardian times. It also organised lucrative special events, such as matinees at leading West End theatres, the proceeds of which were donated to the Hospital.

By 1900, the Dinners were in decline and the aristocracy were no longer such a profitable source following the agricultural depression of the 1890s. The Hospital was able to fill the gaps by attracting more income from official bodies such as the King’s Fund, the Metropolitan Hospitals Sunday Fund, and the leading Temperance organisations.

The Astor family gave £50,000 in 1902 to endow a new out-patients department, whilst two large-scale public events, the Imperial Coronation Bazaar (1902), and the Midsummer Fair and Fete at Olympia (1909) enjoyed the support of most of London’s “high society”. The Hospital was able to utilise the public interest in the events to raise £19,000 and £6,000, respectively. During the First World War, the Hospital was given new rubber flooring for the wards, at the cost of several thousand pounds by the wife of Admiral Jellicoe, the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy.

During the inter-war years, following an abortive attempt to raise £1,000,000 for a completely new country hospital at Beaconsfield, efforts were concentrated on the rebuilding programme, the most significant contribution being J. M. Barrie’s gift of the “Peter Pan” copyright in 1929. Barrie’s contribution helped to stimulate other support from the literary and entertainment worlds: J.B. Priestley helped with the Hospital’s publicity, A.A. Milne wrote publicity leaflets, and other then-well-known novelists such as Bruce Graeme and Ethel Mannin wrote stories for sale in aid of Great Ormond Street. In 1934 the premiere of the film “The Iron Duke” (starring George Arliss as Wellington) raised over £7,000 for the Hospital, thanks to the efforts of London’s leading “society ladies”. In the same year, the Hospital acquired it first artificial respirator, donated by pharmaceutical company, ICI. William Morris, Lord Nuffield endowed the Private Patients unit in the new (Southwood) Building in 1938, and the Hospital received the first of several large donations for new laboratories from its Board-member Sir Stanley Cohen, the owner of Lewis’s, the Liverpool-based chain of department stores (not the same as John Lewis).

Lord Southwood encouraged Shirley Temple to raise the hospital’s fundraising profile in the USA, which later resulted in the “Bombing Book”, circulated to raise money to repair the 1940 bomb-damage to the Hospital. In return for contributions to the rebuilding fund, leading Hollywood actors, actresses and producers, and members of the British and US Governments were offered the chance to add their autograph to the book.

From 1948 until the 1980s, fundraising for NHS hospitals was heavily restricted, but large corporate donations, made through the Institute of Child Health, were still being received.

Notable examples include:

- The Wolfson Foundation (£80,000 for the Wolfson Centre in 1966)

- The Sembal Trust (£250,000 in 1964)

- Sir Michael Sobell (£100,000 via the Variety Club for new research laboratories in 1968)

- Sir Billy Butlin (a new Hydrotherapy Pool in 1966, and a new radiological scanner in 1977)

- The Beaverbrook Foundation (£5,000 towards a new Respiratory Research unit in 1969)

- Hugh Greenwood, founder of the Children’s Research Trust (£80,000 in 1968)

- Sir John Cohen, of Tesco fame (gifts to Great Ormond Street in lieu of 50th wedding anniversary presents in 1972)

The Institute for Child Health’s Annual Reports, published from 1967, list all major donations; there are quite a number each year in the £10,000-£50,000 range.

From the 1940s onwards, the Hospital has also benefited from an amazing array of fundraising activities and supporters: individual Royal Navy Ships have raised money for the hospital; it has had support from Arsenal Football Club (thanks to one the Hospital’s consultants, Dr. Bill Marshall, who also happened to be the team’s physician), and help with individual events from a variety of sportsmen and entertainers. One such event, a fundraising party at Downing Street in 1979, had a guest list which included Penelope Keith, Lulu, Jimmy Saville, Val Doonican, Graeme Garden and Tim Brooke-Taylor.

More recent activities include the famous “Wishing Well Appeal”, the Djanogly Out-Patients Department, supported by donations from the textiles magnate, Sir Harry Djanogly and family, and the foundation of the Botnar Laboratories, in memory of the daughter of business man Octav Botnar.

Nick Baldwin

Archivist